|

Previous Entry

First Entry

|

Latin, Palaeography, and Latin Palaeography

Part One

For a while, I've been toying with the idea of doing a class called something like 'Palaeography for the SCA,' and analyzing SCA scrolls as if they were historical documents and pointing out the features that paleographers use to localize and date manuscripts. It never happened. It occurred to me

that a shorter online format might be good for something similar, and since it's always good to keep

one's hand in with Latin, I decided to mix them all together into this: a combination Latin primer and paleography article, which I hope will be part of a series.

A few basic notes about Latin

Latin is an inflected language, meaning that word endings carry a lot more information than they do in English.

In English, the position of a word in a sentence, along with liberal use of prepositions, help

to identify what the word is doing grammatically. In Latin, the inflection does that job, making

word position much less important, and preposition use less necessary. For example:

- The boy gives the rose to the girl.

- The girl gives the rose to the boy.

- The rose give the boy to the girl.

Those are all correct English sentences, but they all mean different things. And the last one means something strange indeed. In Latin, boy is 'puer,' girl is 'puella,' and rose is 'rosa.' Those

are all in the nominative case, meaning that in those forms, they are the subject of the sentence.

They could also be in the objective case, meaning they are the object of the sentence, and which would be 'puerum,' 'puellam,' and 'rosam.' Or they could be in the dative case, which can mean a couple of things, but often the indirect object. Again, for those nouns, it would be 'pueris,' 'puellae,'

and 'rosae.' The verb 'to give' in Latin, for the third person singular is 'dat.' So the first English sentence above could be any of the following in Latin:

- Puer rosam puellae dat.

- Rosam puellae puer dat.

- Puellae puer dat rosam.

And so on. There are better and worse organizations, of course, but the general principle is sound.

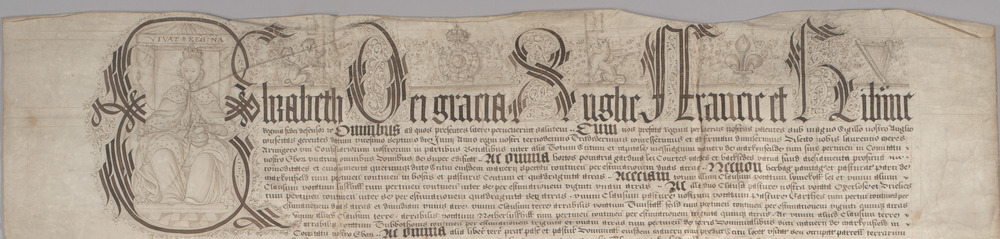

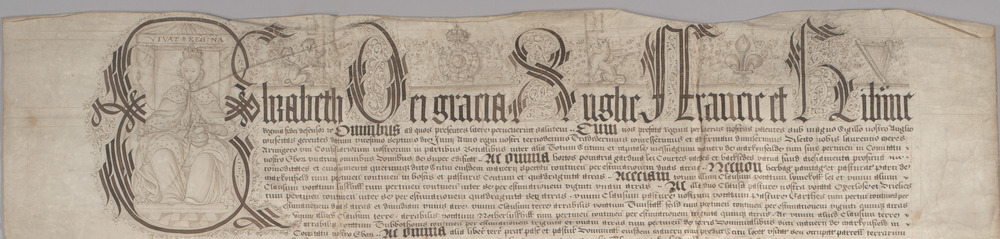

So, let's look at a manuscript. This manuscript is 'dated,' which means just what it sounds like, there's a date on it. Dated manuscripts are very useful to

palaeographers, because they can be used to build up characteristics associated

with a specific time and place. This helps to make some some manuscripts

'datable,' placed within a specific time range. We'll loop back around to this

in a later post.

I don't know where this manuscript is archived, sadly, although it

associated with Markenfield Hall in Yorkshire near Ripon. This manuscript

may be seen in one of their blog posts.

( Click on the image for a larger version in a new window.)

One of the things that is nice about a lot of documents, is that there are

formulae which can help one to get one's eye in on a specific hand. This

document is no exception. The first line is rather elaborate and decorated,

so it may not be as much help later on as we might hope, but we shall press on.

The first three words are 'Elizabeth Dei gracia.' The script is quite formal,

more of a book script than a documentary one. The script changes on subsequent

lines as is quite often the case. Different scripts as well as different sizes

were used to mark sections in manuscripts. I would call this script

something in a Gothic with a high level of execution. (It may be worth noting

at this point, that there are multiple ways of characterizing a specific hand

and script, and I will be fairly casual about it in these posts.)

Looking at the specific letter forms, the z in Elizabeth strikes me

as particularly note-worthy. It is even more compressed than I would

expect in a Gothic script. The D in 'Dei' harkens back to the uncial,

and the ascender is not very distinct. Compare also the t in 'Elizabeth'

with the c in 'gracia.' The stroke of the 't' extends markedly above x height,

and the c does not. This is worth pointing out because the Latin is wrong -

it should be a t - 'Dei gratia.'

Gratia is the ablative case of gratia, which means grace. First declension nouns, such as gratia,

have the same ending the nominative and ablative case. This can be confusing.

Context is important. In the sentence we are looking at, Elizabeth is the

subject, not grace. It's also a well-known formula, which helps. At this

time, scribes were writing not only in Latin but also in the vernacular, English

in this case, and I suspect the scribe simply made the substitution thinking

of the English word grace. The ablative case has many uses, one of which

is sometimes called 'the ablative of means' and often is translated as 'by.'

Dei is the genitive case of deus, god. Or as I'm sure our scribe would think

of it, God. Deus is a second declension noun, and the -i ending could also

mean plural nominative, but, of course, it doesn't. So 'dei gratia' - by grace of God.

The rest of the line is also part of a well-known formula, and reads, 'Anglie (et) Francie et Hib(er)nie.'

The '(et)' is to indicate that the word is not

spelled out, but that the Tironian note is used to indicate 'et.' The '(er)'

is used to indicate that an abbreviation is being used. There is a little

swirl above and between the b and the first minim of the n in Hibernie,

this is one version of the r-something or something-r abbreviation (er, ir, ri, etc). There

were a lot of abbreviations, and they weren't always consistent.

'Anglie,' 'Francie', and 'Hibernie' all end in e. Except they don't, or

rather shouldn't. In classical Latin, the second declension genitive ends

in -ae. In medieval Latin, that often drifted to an e caudata, ç, and

even further to a simple e. Which means that those would read 'Angliae, Franciae, and Hiberniae.' Which is to say, 'of England, France, and Ireland.' The

first word of the next line is 'Regina' ...

I'll close this post with a few more notes about letter forms which I find interesting. There are two a's in 'gracia,' and they have two different forms. The

second, terminal a, is slightly odd, resembling a modern capital A. This form

also appears in Elizabeth. The first is something of a hybrid, resembling

both the common Gothic a, but with a bit of an Anglicana look, at least

to my eye. This form is also used in Francie. In both cases, it is after

an r allowing the scribe to push the letters closer together in the approved

Gothic style. The other a resembles the one used in the subsequent lines.

The scribe has also chosen to 'dot' only a single i - the

one in Hibernie. A slightly odd choice, since it is not in a string of minims.

I'm linking to a Diaspora posting for comments and such.

Comment thread on PlusPora

Anyone should be able to read, but a (free) account will be needed to post.

|

Next Entry

Latest Entry

|

![Smashy the Hammer hates cell phones [Smashy the Hammer]](/hammer.gif)

![Of course there is mouseover text, because, hey, aspiring. [An Aspiring Luddite]](/Luddite2.gif)

![I am looking at my off-camera

bass guitar [Jeff Berry]](/file.jpg)